Stakeholder Workshop Report: Process for Establishing Release Limits and Action Levels at Nuclear Facilities

Table of Contents

Topic Areas and Discussion Summaries

1. Technology-based Release Limits - BATEA - Pollution Prevention

Appendix B: Workshop Participants

Appendix C: General mixing Zone Limits in Quebec, Saskatchewan and Alberta

D.1 Technology-based Release Limits - BATEA - Pollution Prevention

D.2 Exposure-based Release Limits and Mixing Zones

How to Comment

You may provide your comments:

- email: consultation@cnsc-ccsn.gc.ca

- mail:

Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission

P.O. Box 1046, Station B

280 Slater Street

Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1P 5S9 - Fax: 613-995-5086

Comments submitted, including names and affiliations are intended to be made public. You will not receive a formal reply to your comments.

Introduction

The Commission has charged staff of the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) to review the existing framework for regulating release limits of nuclear substances as well as to develop and document a formal framework for establishing regulatory release limits for hazardous substances at CNSC-licensed facilities.

In response, the CNSC released Discussion Paper DIS-12-02, entitled Process for Establishing Release Limits and Action Levels at Nuclear Facilities, in February 2012 for public comment. Due to the interest in the discussion paper, the standard 60-day review period was extended for an additional 60 days to June 30, 2012. Comments received were posted on the CNSC Web site for a standard 30-day comment period. Once again, upon request, this secondary comment period was extended for an additional 30 days to September 30, 2012.

This public review process generated extensive comments from industry, federal and provincial regulatory agencies, and non-governmental organizations. A summary What We Heard Report was posted on the CNSC Web siteFootnote 1.

Given the diversity of the comments received, CNSC staff recognized that additional consultation and discussion would be required prior to determining a path forward. Additional consultation was intended to provide stakeholders with an opportunity to clarify their comments on specific aspects of the CNSC's proposed approach for establishing release limits and action levels (ALs) at nuclear facilities.

To this end, CNSC staff organized a one-day workshop with the stakeholders who had provided comments on the discussion paper. Invitations to participate in the workshop were sent separately to 30 responding organizations and individuals. This workshop took place in June 2013. A total of 28 people participated, the majority representing industry sectors including mining and milling, fuel fabrication, nuclear power plants, research and development, and waste management. Other participants were private consultants and representatives of a non-governmental organization (CSA Group) and a federal regulator (Environment Canada).

The workshop was structured around four topic areas designed to cover those areas of the discussion paper that sparked the most discussion. These topic areas were:

- Technology-based Release Limits, BATEA and Pollution Prevention

- Exposure-based Release Limits and Mixing Zones

- Release Limits Based on Radiation Dose to the Public

- Action Levels for Environmental Protection

Prior to the meeting, information packages outlining each of the topic areas were provided to registered participants. This information is contained in the report below, as the lead-in to each discussion summary. The workshop opened with a brief presentation by CNSC staff reflecting the What We Heard Report, which had been posted to the Web site, and an explanation of the workshop procedures for the day.

Participants were pre-assigned to groups to ensure diversity of interest and expertise for each discussion session. Each group remained intact and rotated as a team through each of the four topic areas during the day. Each topic table was facilitated by a CNSC staff member who encouraged discussion and documented participant comments.

At the end of the day, the four facilitators presented a summary to all workshop participants for validation and to obtain any final feedback. These summaries and the original notes from the flip charts are provided in the following pages. It should be noted that the summaries and notes represent the positions or opinions of the workshop participants and not those of the CNSC. CNSC staff have not yet finalized their assessments of the comments received to date on the proposed process to establish release limits and ALs.

CNSC staff are now making this workshop report available to all stakeholders for another opportunity to comment on the proposed approach to regulating releases of effluents to the environment. A list of acronyms used in this document is found in Appendix A, and a list of participating organizations is found in Appendix B.

CNSC staff will carefully consider all comments received from stakeholders to develop the CNSC regulatory approach for establishing release limits and action levels at nuclear facilities. Stakeholders and the public will have an opportunity to comment on the resulting approach.

Topic Areas and Discussion Summaries

1. Technology-based Release Limits - BATEA - Pollution Prevention

1.1 Background Information

Environmental Legislation in Canada, including that of the NSCA, operates beneath the overall umbrella legislation of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA).

Short Title: "An Act respecting pollution prevention and the protection of the environment and human health in order to contribute to sustainable development"

Preamble: Whereas the Government of Canada is committed to implementing pollution prevention as a national goal and as the priority approach to environmental protection;

CNSC Regulatory Policy Protection of the Environment (P-223):

"This regulatory policy describes the principles and factors that guide the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) …. in order to prevent unreasonable risk to the environment in a manner that is consistent with Canadian environmental policies, acts and regulations and with Canada's international obligations."

In this context it is proposed that release limits be established based on effective and demonstrated pollution prevention/control technologies/techniques or the limits required to meet risk-based and scientifically defensible ambient environmental quality guidelines, whichever are more stringent.

The use of pollution prevention performance standards, such as that of Best Available Technology Economically Achievable (BATEA), is a common regulatory expectation both internationally (e.g., European Union BAT documents, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA) Expert Group on BAT, US EPA etc), nationally (e.g., Metal Mining Effluent Regulations (MMERs)), and provincially (Alberta, Ontario, Quebec). BATEA-based limits generally consist of reviewing the achieved effluent performance of facilities using BATEA (not necessarily the same technology or techniques) and determining a concentration (or activity level) which can be achieved. Hence, BATEA-based effluent limits do not determine the specific technology/technique but rather specify the minimum expected performance. The operator may then determine the technology/technique they wish to apply.

The Commission has charged staff with establishing wherever feasible a minimum common standard of effluent quality applicable to CNSC regulated facilities (all or sector based).

1.2 Issue

How should the concepts of BATEA and pollution prevention be incorporated into an effluent quality decision framework.

Proposal: Use BATEA-based technology-based release limits (TBRLs) where site-specific factors indicate no need for further improved effluent quality.

Many of the release limits found in Canadian Federal and Provincial legislation are BATEA-based. The CNSC proposes to use limits that presently exist in federal and/or provincial legislation. These limits do not account for site-specific sensitivities nor the assimilative capacity of the receiving environment. As such they are considered minimum effluent performance requirements representing a commitment to pollution prevention, the priority approach to environmental protection. For example, a facility releasing effluent to a waterbody with the assimilative potential of one of the Great Lakes is unlikely to have a risk based effluent concentration as immediate dilution potential is so high (especially with diffusers). In such scenarios existing BATEA-based effluent limits would establish the minimum quality of the effluent.

The discussion document also proposed that all new facilities incorporate BATEA during the design phase.

1.3 Questions for Discussion

- What would be the impediments to the use of BATEA-based limits in legislation with the expectation that facilities incorporate BATEA into their facility designs (independent of risk)? If so what are potential alternatives?

- What would be the impediments to the use of available (i.e., existing federal and/or provincial legislation) sector specific technology-based release limits (i.e., minimum performance standards) unless site-specific factors indicate the need for stricter exposure-based limits?

- What would be the impediments to the use of case specific technology-based release limits as described in the discussion document?

- How should BATEA be determined and at what frequency should it be reviewed?

1.4 Summary of Discussion

- Participants agreed in principle on the link between "pollution prevention" - ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable)- and a "technology-based solution".

- They do not want the technology-based "solution" to be a limit.

- Could the exposure-based release limit (EBRL) be considered as the limit, but technology-based release limit (TBRL) as the "objective?" This "objective" could be introduced as a separate process that could be inspected, reviewed and enforced to ensure pollution prevention. The purpose would be to "control performance". The EBRL would be used to control safety.

- A parallel would be radiation protection that relies on limits, but uses ALARA to continually optimize processes to reduce exposures - it is recommended to use EBRL for a limit and a program based on TBRL as the "ALARA" program.

- There is concern over what triggers would require a retrofit when a new technology comes along - in the absence of risk.

- TBRLs may require treatment when there is no risk to avoid or minimize. This may result in increased energy consumption, use of additional process chemicals and cost. This could cause an increased environmental footprint.

- The framework must incorporate a holistic approach to establishing limits and avoiding a larger footprint.

- Unnecessary treatment may result in a large quantity of sludge that must be managed post-operation.

- Treatment may require the use of Fe-addition, and Fe may be in the MMERs in the future.

- TBRL may introduce costs with no benefit.

- The best available technology economically achievable (BATEA) for element A may increase the concentration of element B.

- A very simple framework is needed for discerning between "risk" and "performance improvement" and how the two relate to limits.

- Participants commented on impediments to the use of existing limits.

- Limits could be outdated.

- The public may not understand/know the science behind limits (and whether or not the limits are protective).

Additional participant comments (flip chart notes) are available in Appendix D.

2. Exposure-based Release Limits and Mixing Zones

2.1 Background Information

The CNSC has had to require treatment for hazardous substances that have either:

- been determined to be CEPA toxic, or

- identified as posing an "unreasonable risk" based on site-specific risk assessments.

Without a well established regulatory approach for the development of licence limits the CNSC has used Action Levels (ALs) as "informal" licence limits. This is an inappropriate use of ALs and does not represent clear regulatory requirements.

The Commission has determined that this is no longer acceptable and charged staff to identify and adopt a protocol for developing CNSC licence limits for such substances.

2.2 Issue

How should limits be established for substances for which there are no regulatory limits in existing federal or provincial legislation or CNSC licencesFootnote 2.

Proposal: Use exposure-based release limits and mixing zones

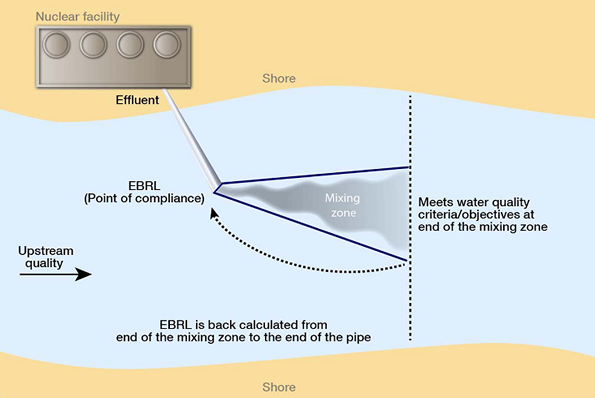

The basic principle for an exposure-based approach is to determine the criteria to be attained at a specific distance from the point of release and to back-calculate the concentration that would need to be achieved in the effluent to ensure the desired concentration at the specified point in the receiving environment is not exceeded. A liquid effluent example taken from the discussion document is provided.

For atmospheric releases of hazardous substances the release limit is often based on determining the point at which ambient air quality criteria or point-of-impingement criteria are to be achieved with this determining the "mixing zone". This atmospheric mixing zone represents an area within which criteria (almost always chronic) may be exceeded, however, this is generally acceptable as the mixing zone by its nature is in the air and does not contain resident human or non-human biota.

Figure 1: Representation of a back-calculation performed when determining EBRLs

Figure 1 Text alternative | Larger image for Figure 1

Exposure-based release limits incorporating mixing zones for liquid releases to the aquatic environment is also a common practice used internationally and by provincial and territorial regulatory authorities in Canada. The CNSC proposed methodology is based on documentation provided by the US EPA to state water regulatory authoritiesFootnote 3 and Canadian provincial environmental regulatory documentation such as that of Alberta, Ontario and Quebec which themselves are based on the US approach.

Unlike the atmospheric releases, aquatic mixing zones must address two issues:

- there is a higher likelihood of having aquatic life resident within the mixing zone, thus the acceptable spatial extent of the mixing zone needs to be defined, and

- there is the potential for conflict with the Fisheries Act (s.36) which prohibits the discharge of deleterious substances and does not recognize "mixing zones".

2.3 Questions for Discussion:

The main issues to be discussed with respect to mixing zones are:

- What approaches should the CNSC consider when EBRLs need to be established for hazardous substances released to the atmosphere?

- What approaches should the CNSC consider when EBRLs need to be established for hazardous substances released to the surface water?

- In the context of EBRLs for discharges in headwaters of watersheds, how can provincial or federal guidance on mixing zones be used?

- For EBRLs, exposure-based criteria need to be identified. What would be the appropriate criteria for human health (non-carcinogens and carcinogens)? What would be the appropriate criteria for biota (aquatic organisms and wildlife)?

A table of general mixing zone limits in Quebec, Saskatchewan and Alberta is provided in Appendix C.

2.4 Summary of Discussion

- Participants commented on duplication of oversight by multiple regulators.

- The document [discussion paper] needs to be clear regarding harmonization and how it would be achieved.

- All regulators need to reach agreement on the location of the "point of release".

- Definitions of cancer risk for EBRL need to be harmonized with those of Health Canada.

- There is potential conflict with subsection 36(3) of the Fisheries Act, which does not recognize mixing zones.

- New tools are being considered that may allow the recognition of limits established by other governmental agencies (provincial or federal) if it can be demonstrated that the risks are low and have been fully assessed, and that regulatory instruments are in place to enforce them.

- Is there a role for chronic, sub-lethal toxicity tests in regulating release limits?

- The definition of "mixing zones" must consider seasonality, low flow under climate change, site-specific factors, etc.

- How is uncertainty (at all levels) addressed in EBRLs?

- The discussion paper was not clear that EBRLs would apply only to hazardous substances; the paper needs to be clear that dose modelling/predictions to non-human biota may not be advanced enough (scientifically) to develop EBRLs.

- "Accepted" impacts in an approved environmental assessment/environmental risk assessment (EA/ERA) must be used to define the extent of an acceptable mixing zone and point of compliance for a mixing zone.

- Who will do the "work" and expend the resources to develop EBRLs? The licensee? CNSC? What about the public perception if the licensee develops their own EBRL?

- EBRLs should be used to define what is "safe" based on the EA/ERA. Then, in most cases, below that should be a TBRL or "objective" for treatment in the spirit of pollution prevention and ALARA.

Additional participant comments (flip chart notes) are available in Appendix D.

3. Release Limits and Dose to Public

3.1 Background Information

In the past it was common for the CNSC to base authorized radiological release limits on the public dose limit of 1 mSv/yr. In some instances this resulted in:

- release limits that could only be exceeded under major accident scenarios;

- the difference between the authorized release and the actual release differed by orders of magnitude;

- the release limit exceeded the facilities entire inventory of the radionuclide.

In such cases the release limits:

- fail to serve the intended control objective; and

- leave the perception that regulatory authorization has been provided for the operator to discharge substantially greater quantities of radioactivity than the facility has been designed to release.

It is recognized that too low a difference between actual and authorized releases may result in operators breaching an authorized discharge rate when carrying out reasonable and necessary activities which, while having negligible radiological impacts, could raise substantial concern within the public and lead to the perception of poor regulatory performance.

In response to public and Commission concerns with respect to these large discrepancies between authorized releases and actual releases, licence release limits for some facilities have been based on values other than 1 mSv/yr.

Thus, presently the CNSC is using a non-uniform approach for the determination of release limits with respect to the dose to public.

- Nuclear power plants based on 1 mSv/yr

- Fuel Fabrication Facilities based on 0.05 mSv/yr

- Tritium Processing Facilities based on 0.05 mSv/yr

- Uranium mines and mills release limits are TBRLs in federal or provincial regulations (Saskatchewan's Mineral Industry Environmental Protection Regulations and the federal MMERs). Compliance with the 1 mSv/yr regulatory limit is demonstrated in Environmental Assessments and periodic Status of the Environment Reports.

3.2 Issue

How should derived release limit (DRL) -based release limits (CSA N288.1 Guidelines for calculating derived release limits for radioactive material in airborne and liquid effluents for normal operation of nuclear facilities) be calculated to serve as facility control values, while still providing adequate margin to allow for operation flexibility and response to non-routine plant conditions?

Proposal: Calculation of DRLs using a dose value/criteria other than the public dose limit in the NSCA

3.2.1 International Best Practice

Internationally, practices vary, though a number of countries use the DRL approach with the modelling based on a value other than the 1 mSv/yr public dose value/criteria in regulation. The specific values vary from 0.3 mSv/yr to 0.1 mSv/yr. Others base licence limits on actual releases, tightening limits as performance improves.

The OECD NEA Expert Group on BAT has recently (2012) released a report entitled: "Good Practice in Effluent Management for Nuclear Power Plant New Build."

This document, in the paragraph provided below, concisely summarizes the challenge being faced.

"The challenge is to devise a transparent and consistent approach to setting authorised discharge rates at levels that are stringent enough to guarantee a high level of performance in relation to discharges, while giving operators the flexibility they need to conduct normal, acceptable operations and/or to respond to non-routine plant conditions without infringing their discharge authorisations."

NEA provides the following guidance:

Principles for use in those countries where the regulatory authority establishes (or approves the operator's application for) authorised discharge limits at levels below those required by consideration of annual dose limits. Authorized limits should:

- … be based on the levels of discharge … determined to be optimised for plant operation, considering the discharge abatement techniques available to the operator. …

- … provide for necessary operator flexibility based on fluctuations or trends in the levels of discharge over time, that the operator has substantiated will occur in routine operation and anticipated operational occurrences (e.g., start-ups, leaks and malfunctions expected to occur during the operating lifetime of the plant), even though BAT have been applied.

- The difference allowed between actual discharges and prospectively authorised discharge rates should be kept near the minimum necessary for the normal operation of the plant (routine operations and anticipated operational occurrences).

- The authorised discharge rates are not set at levels corresponding to the boundary between acceptable and unacceptable radiological impact or to a calculated value of dose to members of the public equal to the annual dose established in traditionally set generic discharge limits. In particular, they do not correspond to the dose limits contained in national or international legislation. The application of BAT should in all likelihood have eliminated any proposals which would give rise to calculated doses approaching or exceeding such limits before the stage is reached when authorised discharge rates are established.

3.2.2 IAEA Safety Standards Series - Safety Guide No. WS-G-2.3: Regulatory Control of Radioactive Discharges to the Environment

The IAEA Safety Guide was published in 2000 and provides substantial guidance on setting release limits that have been summarized by the statements below:

- "Authorized discharge limits are set by the regulatory body."

- "The limits shall satisfy the requirements for the optimization of protection and the condition that doses to the critical group shall not exceed the appropriate dose constraints."

- "They should also reflect the requirement of a well-designed and well managed practice and should provide a margin for operational flexibility and variability."

- "In order to satisfy these requirements, the numerical values of the authorized discharge limits should be close to, but generally higher than, the discharge rates and quantities resulting from the calculations for optimization of protection to allow margin for operational flexibility, although they should never exceed the discharge level corresponding to the dose constraint."

- "Discharge limits will be written and attached or incorporated into the authorization and will become the legal limits with which the operator or licensee should comply."

- "The discharge limits can refer to the complete spectrum of radionuclides to be discharged, or nuclides can be combined in appropriate groups such as, for example, noble gases or halogens. Limits for specific nuclides might be adopted if the radionuclides are radiologically significant, if they are major contributors to the discharges or if they serve as indicators of plant performance."

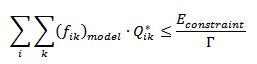

- "the values selected should not exceed those corresponding to the dose constraints; i.e. they should satisfy the following condition:

where

![]()

is the maximum future annual dose to the critical group, calculated with a particular model and for the discharge of radionuclide or radionuclide group i by discharge route k per Becquerel

![]()

is the discharge limit, in Becquerels, on the annual release of radionuclide or radionuclide group i by discharge route k

![]()

is the dose constraint for the source under control.

![]()

is a safety factor to take account of the uncertainty in the model used to calculate doses so as to provide sufficient confidence that the source related dose constraint will not be exceeded"

3.3 Questions for Discussion

- Are there any impediments to establishing authorized DRLs using international best practices (NEA, IAEA)? If so, what are potential solutions?

- What approaches can be used to take into account operational flexibility, including non-routine plant conditions?

- Taking into consideration the different sectors that the CNSC regulates, how should the dose criteria be defined?

- Does optimization have a role to play in identifying the dose criteria? If so, is guidance on optimization needed?

- Are there impediments to calculating DRLs for uranium mines and mills? If so what are potential solutions?

3.4 Summary of Discussion

- The importance of keeping the 1 mSv/yr derived release limit (DRL) was emphasized by a number of groups. A number of workshop participants expressed concern that the public would erroneously interpret the use of a lower dose for calculating release limits as an indication that the public dose limit of 1 mSv/yr was not adequately protective.

- A suggested alternative was to keep the 1 mSv/yr DRL, but establish another value between the DRL and AL that represents an unacceptable loss of control related to the proper operation of the facility. Within this framework it is important to:

- carefully choose the terms (DRL vs. limit vs. value vs. level) and associated definitions

- be flexible/universal, consistent with international best practices, take a defence-in-depth approach, and avoid redundancy with ALs

- consider applicability to new vs. existing facilities and how cumulative dose would be dealt with

- consider the approach to implementation and compliance (e.g., the possibility of administrative monetary penalties and/or increased monitoring and reporting expectations)

- consider means of application to facilities that already have dose constraints in licences - whether this conceptual framework should be advanced (e.g., much higher or lower relative to values in licences)

- Application to mining is unclear.

- From a mining perspective, too low a dose value that represents loss of control could result in an increased footprint and increased energy costs, making projects uneconomical.

- With respect to the present situation for Northern Saskatchewan mining, it is difficult to define "public" due to remoteness of facilities. It was suggested to use very conservative assumptions for defining a representative member of the public and to continue to calculate dose in mining environmental assessments.

Additional participant comments (flip chart notes) are available in Appendix D.

4. Action Levels for Environmental Protection

4.1 Background Information

In the context of environmental protection, the purpose of action levels (ALs) is to ensure, in addition to maintaining releases below licence limits, that the licensee demonstrates "adequate control" of its facility and internal processes by maintaining releases within the "normal operating range". This would be defined by its accepted facility design and engineering and administrative controls. The AL should identify when a "potential loss of control" may be occurring such that specific action may be taken to prevent a loss of control.

To define the "normal operating range" and to identify if the operation is outside of it, ALs can be derived using statistical methods that consider the variability of the contaminant levels in the releases, and that represent performance at the upper end of the facility's normal operating range for which an exceedance could indicate potential loss of control.

ALs serve to:

- identify when the quality of releases may be deviating from the normal operating range and thereby indicate a potential loss of control (before an actual loss of control occurs)

- identify fluctuations in concentrations of contaminants that may be deviating from their normal operating range (e.g., a change in waste stream characteristics)

- provide for process control feedback such that timely actions may be taken to return the process to normal operating range

The CNSC proposes that ALs be established for all Class I facilities, uranium mines and mills and waste management facilities which have controlled points of release.

The only current guidance related to developing and implementing ALs is provided in CNSC regulatory guide G-228, Developing and Using Action Levels (2001). This guide focuses on the use of ALs within the radiation protection program (predominantly for workers) rather than environmental protection in general. It does not provide specific guidance for numerically deriving ALs. This has led to inconsistencies between the derivation and application of ALs on releases among and within the various types of facilities licensed by the CNSC. Some licensees have calculated their ALs using statistical procedures applied to actual operating performance data and others have simply selected values below the licence limits with no specific relationship to actual operating performance (e.g., percentage of the licence limit). In the latter situation ALs for some facilities represent levels that would only be exceeded if a severe loss of control had occurred. This defeats the purpose of an AL which is to take action should there be indication of a "potential" loss of control to ensure on-going control of releases within the normal facility performance.

4.2 Issue

Identify a standardized approach for developing Action Levels

Proposal: Action levels for environmental protection will be statistically derived (scientifically justifiable)

The CNSC proposes that the protocol for establishing ALs for operational control involve statistical process charting, which would indicate when effluent quality may be deviating from that expected under normal operating conditions. Since these levels would be statistically determined from predicted or actual operating data, they may need to be fine-tuned over the licensing period as performance of the facility improves with increased operating experience or varies with minor process changes. Hence, unlike licence release limits (which should remain relatively fixed), properly determined ALs may vary over time.

The CNSC position is that Action Level derivation shall be standardized and shall be statistically based. However, CNSC staff are aware that there are an number of issues that must be addressed to ensure that the statistical approach is flexible enough to meet the needs of the broad industry sector regulated by the CNSC.

Within the Discussion Paper an example of a possible statistical approach was provided along with a number of issues that CNSC staff were seeking input on.

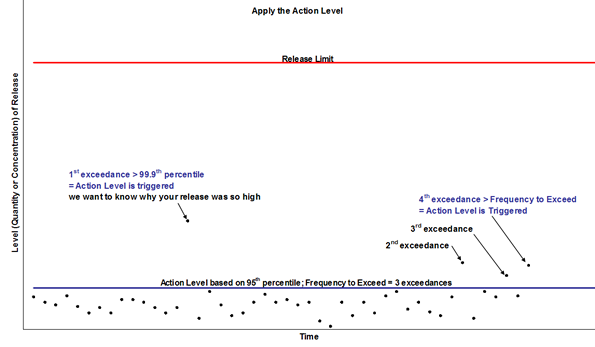

The proposed methodology is scientifically defensible, transparent, and would be an effective tool for predicting a potential "loss of control" of a licensee's environmental protection programs. An example of the methodology for developing an action level as well as its triggering is presented below:

4.2.1 Action Level Example

Three graphs are presented in Figures 2-4, outlining the graphical outputs of the proposed methodology used to develop environmental action levels.

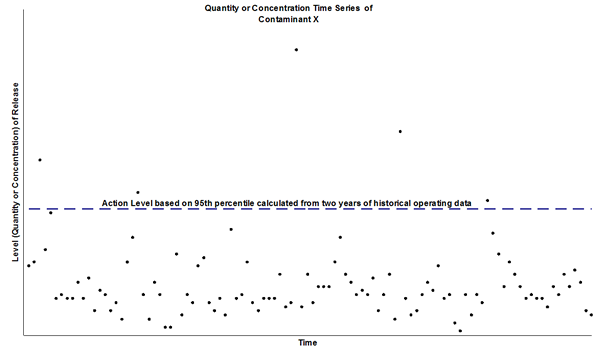

Figure 2 depicts a scatter plot time series, which is the output of the first step of the proposed methodology. The plotted dataset represents two years of weekly sampling data, or approximately 104 scatter points. The concentration or quantity of a Contaminant X that is released to the environment is presented on the y-axis, with time on the x-axis.

A broken line showing the concentration of the 95th percentile of the dataset is also presented on the graph. The text "Action Level based on 95th percentile calculated from two years of historical operating data" is provided directly above the line. There are five scatter points with values above the 95th percentile at various periods of time, which is what would be expected with 100 samples of data (i.e., 5 out of every 100 samples would be expected to be above the 95th percentile). The upper right corner of the graph outlines the details of Step 1:

Step 1:

- Plot the quantity or concentration of the contaminant, based on at least two years of historical operating data to construct a time series.

- Identify periods of known upset to exclude from the data set.

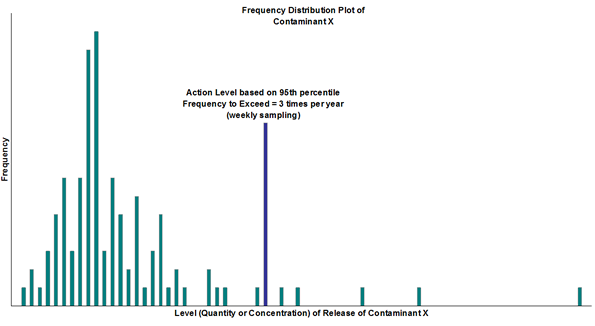

Figure 3 depicts a Frequency Distribution Plot of Contaminant X, in the form of a vertical bar graph for the same two-year dataset shown in Figure 2, and is the output of the second step of the proposed methodology.

A frequency distribution plot is used to depict the number of samples or values having a specific concentration or quantity or range of concentration or quantity. The frequency is plotted on the y-axis and the concentration or quantity of Contaminant X is plotted on the y-axis. A frequency distribution plot can help visually determine the type of distribution and any outliers. For environmental release data, the distribution will typically follow a normal or positively skewed log-normal distribution. The frequency distribution plot can also help identify if there are multiple data populations within the dataset.

The graph depicts a positively skewed logarithmic distribution, where the peak and approximately 95 percent of the concentration or quantity of Contaminant X are located towards the left side of the graph, and fewer samples (having higher concentrations or quantities) are scattered towards the right of the graph. A vertical bar line representing the concentration at the 95th percentile of the data is also presented on the graph, with the text "Action Level based on 95th percentile, Frequency to Exceed = 3 times per year (weekly sampling)," provided directly above the line. There are five bars with concentrations above this line. The upper right corner of the graph outlines the details of Step 2:

Step 2:

- Construct a Frequency Distribution Plot of the Data.

- Identify the type of statistical distribution (normal or lognormal).

- Calculate statistical parameters (i.e., arithmetic mean, arithmetic standard deviation, coefficient of variation).

- Calculate Action Level based on some percentile of the statistical distribution using appropriate equations.

- Determine the statistically predicted "Frequency to Exceed" the action level (i.e., if 50 samples are taken in a year, then the frequency to exceed an Action Level based on the 95th percentile is 2.5 times or approximately 3 times a year.

Figure 4 shows weekly operational data presented on a scatter plot time series for 46 weeks of operation within a year. The graph is used to demonstrate when the action level would be triggered, and hence reporting to the CNSC. As in the first graph, the concentration or quantity of Contaminant X that is released to the environment is presented on the y-axis, with time on the x-axis.

A solid line depicting the action level based on the 95th percentile is plotted. Text above the line reads "Action Level based on 95th percentile; Frequency to Exceed = 3 exceedances", implying that three exceedances would be expected, and that the action level does not trigger until a fourth exceedance occurs.

With each scatter point representing one week, the first exceedance does not occur until the 15th week. The second exceedance occurs during the 40th week and the third exceedance occurs during the 44th week. As three exceedances are expected in a year for weekly sampling, the action level is not triggered. On week 46, a fourth exceedance occurs and triggers the action level, along with the requirement to notify the CNSC and conduct an investigation. This requires taking any corrective and/or preventative measures needed to restore the effectiveness of the environmental protection program and bring the system back to normal operation, based on its approved facility design.

Also to note, the first exceedance is much higher than the other three, being slightly above the 99.9th percentile. Text above the first exceedance states "1st exceedance > 99.9th percentile = Action Level is automatically triggered. We want to know why your release was so high." This reflects the use of the 99.9th percentile to immediately capture any statistically significant deviations from normal operation.

Step 3:

- Monitor the levels of release and identify when an exceedance occurs.

- If an individual exceedance occurs, an internal investigation is recommended.

- If an exceedance occurs more times than the predicted "Frequency to Exceed", or is above the 99.9th percentile, then the action level is triggered and the licensee must conduct a formal investigation and report to the CNSC.

Figure 2: Example a Time Series plot of historical release data for the calculation of an action level, based on the 95th percentile of the operating performance of a specified facility

Figure 2 Text alternative | Larger image for Figure 2

Figure 3: Example of a Frequency Distribution Plot

Figure 3 Text alternative | Larger image for Figure 3

Figure 4: Example of the implementation of an action level, and under what conditions it would be triggered (i.e., a single exceedance of the 99.9th percentile or an exceedance greater then the frequency to exceed the 95th percentile)

Figure 4 Text alternative | Larger image for Figure 4

4.3 Questions for Discussion

The core proposal is that the methodology for deriving Action Levels is to be standardized and based on a statistically defensible methodology.

It is however, recognized that there are a number of technical issues that must be addressed to define the most appropriate statistical approach. The CNSC agrees with industry recommendations that a CSA Standard development process be undertaken to address these issues.

Issues that will need to be addressed and are proposed for further discussion in this workshop include:

- Are there any impediments to using the proposed approach? If so what are potential solutions?

- What operational characteristics should be taken into account when choosing the percentile to be used for developing the AL?

- Periodic exceedances can be expected for statistically derived ALs. For this approach what should constitute an exceedance of an AL?

- Is the "frequency to exceed approach" considered a feasible methodology to setting ALs?

- If so does there also need to be an upper bound value incorporated into the frequency to exceed approach?

- How should characteristics associated with batch and continuous releases be accounted for in the methodology?

4.4 Summary of Discussion

- The CNSC needs to provide clarity on the role/definition of action levels.

- The CNSC's position on consequences of exceeding ALs needs to be clarified, e.g., reporting to a licensing officer, reporting to the Commission, Web site notification.

- Language used - risk language vs. control language. There were different positions among participants:

- Implication of ALs used to inform risk: exceedance represents a concern with respect to health and safety.

- Implication of ALs used to inform or demonstrate good operational control: exceedance represents no health and safety concern.

- There should be a consistent methodology that is representative of the role/definition as determined by the CNSC, free from unnecessary complexity and easy to communicate to the public. The CNSC should clarify that values are site-specific based on approved facility design and operation.

- A single standard approach may not be applicable to the wide range of facility types in the nuclear fuel cycle.

- Let ALs be a process to drive down releases. Serve as site-specific operational practices of pollution prevention.

Additional participant comments (flip chart notes) are available in Appendix D.

Appendix A: List of Acronyms

- AL

- action level

- ALARA

- as low as reasonably achievable

- AMP

- administrative monetary penalty (Nuclear Safety and Control Act)

- BAT

- best available technology

- BATEA

- best available technology economically achievable

- CNSC

- Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission

- COPC

- contaminant(s) of potential concern

- CSA

- CSA Group

- DRL

- derived release limit

- EBRL

- exposure-based release limit

- EC

- Environment Canada

- EPA

- Environmental Protection Agency (United States in this context)

- EA

- environmental assessment

- ERA

- environmental risk assessment

- IAEA

- International Atomic Energy Association

- ICRP

- International Commission on Radiological Protection

- IIL

- internal investigation level

- MISA

- Municipal-Industrial Strategy for Abatement (Ontario)

- MIEP

- Mineral Industrial Environmental Protection Regulation (Saskatchewan)

- MMER

- Metal Mining Effluent Regulations (Canada: federal)

- NEA

- Nuclear Energy Agency (of the OECD)

- NPP

- nuclear power plant

- OECD

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- TBRL

- technology-based release limit

Appendix B: Workshop Participants

| Organization | Number | Role |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Director General of DERPA 2: Directorate of Environmental and Radiation Protection and Assessment 3: Regulatory Policy Analysis Division | ||

| AREVA Resources | 3 | Participant |

| Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd. | 2 | Participant |

| BHP Billington | 1 | Participant |

| Bruce Power | 2 | Participant |

| Cameco Corp. | 4 | Participant |

| Canadian Nuclear Association | 1 | Participant |

| Canadian Standards Assoc. | 1 | Participant |

| Denison Environmental | 2 | Participant |

| ECOMETRIX | 1 | Participant |

| Environment Canada | 1 | Participant |

| NB Power | 1 | Participant |

| Ontario Power Generation | 3 | Participant |

| Rio Tinto | 4 | Participant |

| SENESConsulting | 1 | Participant |

| TRIUMPH | 1 | Participant |

| CNSC:DG1 and Lead Technical Advisor | 2 | Specialist Support |

| CNSC:DERPA2 Specialists | 4 | Table Facilitator |

| CNSC:DERPA Administrative Assistant | 1 | Logistical Support |

| CNSC:RPAD3 | 1 | Logistical Support |

Appendix C: General mixing Zone Limits in Quebec, Saskatchewan and Alberta

| Designated Use | Parameter | Fast-mixing rivers | Slow-mixing rivers | Lakes | Estuaries and CoastalWaters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For uses to be designatedeverywhere (i.e., protection of aquatic life) | Dilution Determination | Critical Low Flow | Modeling | Modeling | Modeling |

| Maximum Dilution Factor | 1 in 100 | 1 in 100 | 1 in 10 A dilution estimated by modeling not exceedingthat which would be allotted to the outlet of the lake during the critical lowflow period; if it exceeds this, the dilution at the outlet of the lake is then retained tocalculate the EDOs. | 1 in 100 | |

| Maximum Proportion ofFlow (without diffuser) | 50% of critical low flow | 50% of critical low flow | N/A | N/A | |

| Maximum Proportion offlow (with diffuser) | 100% critical low flow | 100% critical low flow | N/A | N/A | |

| Maximum Mixing ZoneLength | N/A (rapid mixing) | Half the width of theriver and maximum 300 m length | Distance between thepoint of discharge and the surfacing point of the plume. If the plume does notsurface, the length of the mixing zone is limited to the initial dilutionzone (which corresponds to the limit of the near-field region in a model). | Radius of 300 m | |

| Drinking water sources Recreational watersources | 100% of critical low flow Distance to use | 100% of critical low flow Distance to use | Distance to use | Distance to use |

| Designated Use | Parameter | Streams and Rivers | Lakes and Other Surface Impoundments |

|---|---|---|---|

| For uses to be designatedeverywhere (i.e., protection of aquatic life) | Limited Use Zone | No more than 25 percentof the cross-sectional area or volume of flow nor more than one-third of theriver width at any transect in the receiving water during all flow regimeswhich equal or exceed the 7Q10 flow for the area. Surface water quality objectives applicableto the area must be achieved at all points along the transect at a distancedownstream of the effluent outfall to be determined on a case-by-case basis. | Surface water quality objectives applicable to thatwaterbody must be achieved at all points beyond a radius of 100 meters fromthe effluent outfall. The volume oflimited use zones in lakes should not exceed 10 percent of that part of thereceiving waters available for mixing. |

| Designated Uses | Parameter | Acute (Short-term)Criteria | Chronic (Long-term) Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| For uses to be designatedeverywhere (i.e., protection of aquatic life) | Fraction of Flow | 5% | 10% |

| Spatial Restriction | End-of-Pipe or withadequate justification, 30 meters surrounding outfall. | The more stringent of 10 times stream width forlength or ½ stream width. | |

| Drinking water sources Recreational watersources | Spatial Restriction | Distance to use | Distance to use |

Appendix D: Flip Chart Notes

The following bullet points were collected on flip charts during the workshop.

D.1 Technology-based Release Limits - BATEA - Pollution Prevention

- Effluent limits would likely need to be updated; however, it is unclear at what frequency.

- Use frequency of other jurisdictions when incorporating their effluent limits

- Use 10-year Periodic Safety Review

- Less concerned about the frequency of review and more concerned about the criteria that would be used to change them

- Changes should be done 'collaboratively'

- Mixed messages throughout the document so that the perception of what the CNSC was doing was very different relative to what was said at the workshop

- When TBRL is less than EBRL, there is no benefit, only cost

- Going below EBRL should be voluntary, not enforced

- How is 'economically achievable, defined?

- The question was raised regarding 'what parameters' would need a limit? Statement was made that, if unmitigated, a constituent does still meet surface water quality objectives, then a limit is not necessary

- Are we expecting a retrofit of existing plants with no unreasonable risk or acceptable risk? What is the driver?

- TBRLs should only be used as a limit if EBRL cannot be achieved and it is justified to do so based on an ERA

- Case specific TBRLs may cause a problem with public perception or highlight problems with a regulatory approach

- Concern about the consequences of a part of industry moving to newer technology - would the remainder need to move to that technology even in the absence of risk?

D.2 Exposure-based Release Limits and Mixing Zones

- Make it clear in the Discussion Document, that if a limit exists in legislation, it would be used as a CNSC limit

- During times of CNSC disagreement with provincial regulator or Environment Canada - could we have two different licence limits for one substance?

- Is there really the need for another regulator to address hazardous substances?

- Would prefer to have one regulator per substance rather than duplication

- What if CNSC is not happy with the Provincial limit - would CNSC work with the Province to achieve harmonization?

- Site specific factors are important in defining the mixing zone

- Consider seasonal effects and how they would be addressed in the definition of a mixing zone and compliance point

- Using a mixing zone concept in the establishment of EBRL's is in contradiction with section 36(3) of the Fisheries Act - no mixing zones

- In Ontario - MISA - Electricity Sector limits are based on acute and chronic toxicity as well as technology based limits

- It is important to acknowledge what was accepted at the EA stage in establishing a limit

- What will the CNSC do if the application of the framework comes up with a higher number than what we are currently regulated to? Would they move the limit up?

- How will the waste sector (i.e. Elliot Lake) be dealt with? They have limits and monitoring requirements in their licence but were developed in a very complex manner - also they discharge effluent into already impacted surface water

- How will AECL, as a federal entity, be dealt with when there is no "Provincial Regulator" to achieve harmonization with?

- In Saskatchewan, compliance with air quality criteria at point of impingement is not back-calculated or tied to a corresponding stack limit

- If air quality is already being regulated by the Provinces, why is the CNSC also going to do it?

- If there is a health or ecologically-based limit that is considered 'safe', this should be the EBRL

- Then the TBRL and ALARA should be used to prevent pollution - could be a second limit? Or an objective?

- Communication to the public of the basis for the release limit is key

- Background data must be considered in establishing a compliance metric

'accepted impact' in the EA needs to be included in the consideration of the acceptable extent of the mixing zone - Who will do the work to come up with an EBRL - licensee? CNSC?

- What about the issue of public perception of the licensee coming up with the EBRL? What about the additional resources needed from the licensee to develop EBRL?

- Discussion document was not clear that harmonization with other regulators is fundamental to the approach

- The document needs to emphasize and be clear regarding how harmonization would be implemented for each facility type

- If the CNSC cannot convince fellow municipal, provincial and/or federal regulators of the need to either add a new contaminant limit or modify an existing one, then a limit should not be imposed or changed from what it is currently (i.e. lowered)

- Mining sector does not want to be treated differently in terms of limits compared with other base metal mines

- Would there be EBRL's for facilities that discharge to a municipal sewer?

- Tritium EBRL - complex to try and attribute tritium levels in groundwater/soil/surface water to a stack limit - variety of sources (Chalk River)

- Cancer risks ("acceptable") used to develop EBRL's should be harmonized with Health Canada and any other regulators setting health based limits for hazardous

- How do we deal with public perception for newer facilities located adjacent to existing facilities- if the newer facility has a smaller approved mixing zone will that send a message to the public that it is not as 'clean' as another (older) facility?

- Document was not clear that EBRL's would apply to hazardous only and that radiological would not be back calculated to an end of pipe limit due to scientific uncertainties at this time regarding dose effects on non-human biota

- It appears that the radiological 'release limits' are related to 'loss of control' whereas the hazardous release limits based on an exposure level that would be 'safe'? This seems contradictory

- At power plants there are facilities that operate intermittently or during emergency situations that release contaminants - would they have EBRL's - currently they are generally screened out based on NPRI - basis (another table suggested that the ERA should deal with this?)

- Multiple regulators for one contaminant - at Point Lepreau - they may end up with two different limits for hydrazine - one that recognizes a mixing zone (province) and one that doesn't (Environment Canada) - really want harmonization and for regulators to agree.

- Location of "end of pipe" can change for each regulator - i.e. Point Lepreau has a km long 'discharge channel' that is not recognized by EC

- How does uncertainty get addressed in EBRL? Uncertainty exists at all layers of an exposure-based calculation, how will these be addressed in the final 'limit"?

- Mixing zone definition needs to consider extreme seasonality and climate change

- Currently, the Fisheries Act does not allow an effluent to cause acute lethality and currently does not allow mixing zones

- With the changes to the Fisheries Act, new tools or "enabling packages" may be defined to provide flexibility with Section 36(3); for example, it will be possible for EC to authorize deposits of deleterious substances that are already well controlled at the federal or provincial level, that have been fully assessed and managed through other processes, or that are low risk.

- No equivalency agreements or enabling packages under the Fisheries Act exist at this time but are under development

- Would the CNSC consider chronic or sub-lethal toxicity testing be considered in the establishment and acceptance of an EBRL?

- Would the mixing zone qualify as a "treatment technology"?

D.3 Release Limits and Dose to Public

Group 1

- EBRL scheme using dose instead of concentration? - no, it's related to loss of control

- Relationship between ALs and this new limit

- May need to redefine terms, especially ALs

- Language used in IAEA/OECD publications may help - authorized level versus operational level versus investigative level

- A new limit is problematic for mining - very conservative assumptions used in calculating dose to the public in mining EAs

- Maintain DRL based on 1 mSv/y

- Need clarity between ALs and other limits

- The relationship of AMPs to this new limit and optimization

Group 2

- Redundancy/conflict with statistically-based ALs if too low

- Release limit should based on 1 mSv/yr public dose limit (i.e., acceptable risk)

- Natural radiation versus releases - differentiation?

- Could affect the economic viability of uranium mining

- Optimization / ALARA should be kept separate from dose criteria

- For the ICRP purpose of a dose constraint, there is no rationale for going below 1 mSv/yr in Canada

- Would there be additional requirements (e.g., monitoring, frequency, equipment needed) with a new limit?

- Limit should be consistent with international best practices, including flexibility

- With respect to Canadian regulated facilities that currently have dose constraints in licences, how will this be considered should different limits come out of the proposed framework?

- Control licensees at a level but it isn't considered a limit with formalized oversight, compliance, etc. (NPP perspective)

- Structure the release framework in an analogous way to the Defence in Depth concept

- Framework can be consistent and transparent, yet accommodate sector specifics in the details

- How would a licensee demonstrate compliance?

- Continuous monitoring?

- What would constitute an exceedance?

Group 3

- Communication issue

- Perception

- Regulatory link to Derived Release Limit (DRL)

- Control?

- Safety?

- Release limits should be risk-based and not based on arbitrary dose constraints

- Dose constraints should be linked to control; not to DRLs

- Chalk River and Port Hope are examples of sites with multiple sectors

- IAEA has Action Level (AL) guidance

- Address public perception; not DRLs

- ALs are working well for control

- Consistency in establishing ALs will improve the public perception

- Unacceptable risk versus unacceptable loss of control

- Proposed conceptual framework

- DRL (based on 1 mSv/y)

- Unacceptable loss of control point

- AL

- DRL for argon not clear in Chalk River licence

Group 4

- Redundancy between a new DRL and ALs with respect to unacceptable loss of control

- Communication perspective

- For nuclear power plants (NPPs) an AL "loss of control" is not Fukushima

- Conflict between dose and loss of control in terms of establishing a new DRL

- For decommissioning projects, there is a public perception issue on releases under control and those that aren't (e.g. historical)

- For some decommissioning project, there's often no control over what is contributing to the dose

- How would it apply to a new versus existing facility; it could be a design basis for a new facility and perhaps not apply to existing facilities

- How would cumulative dose be dealt with?

- Could have increases due to multiple facilities

- Would retrofits of existing facilities be needed if a new facility was added?

- For a new DRL, there would be economic concerns with respect to reclaimed land for future development and risk perception

- Difficult to define "unacceptable" loss of control

- For mining, a new DRL could result in an increase in the project footprint and energy costs versus the ability to meet the new limit and the associated benefits

- Uranium mines cannot meet a 0.05 mSv/y limit

- What would be the differences in information coming out the exceedance of an AL versus a DRL

- Potential challenges in communications if there are sector and/or site-specific values

- How is the "adequate protection" term under an AL related to the new DRL?

- Need clarity in definitions around limits and levels

- Need alternative wording to "loss of control" due to public perception

- There is a public perception issue around limits and releases of a single unit station versus a multi-unit station as this fact is often not grasped by the public

- What resources will be needed to meet this requirement (i.e., reporting)?

- The limit should be optimized based on risk; not different for each release point in a watershed

- A dose constraint is not a limit or loss of control

- A new limit could impact the cost-benefits of uranium mining in Canada

Footnotes

- http://www.nuclearsafety.gc.ca/eng/acts-and-regulations/consultation/completed/dis-12-02

- Also required when an existing limit in legislation or licences is inadequately protection (e.g. Saskatchewan U and Se limits).

- EPA National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES)

Page details

- Date modified: